Summary of “Relevant Research Areas in IT Service Management: An Examination of Academic and Practitioner Literatures” (Marrone & Hammerle, 2017)

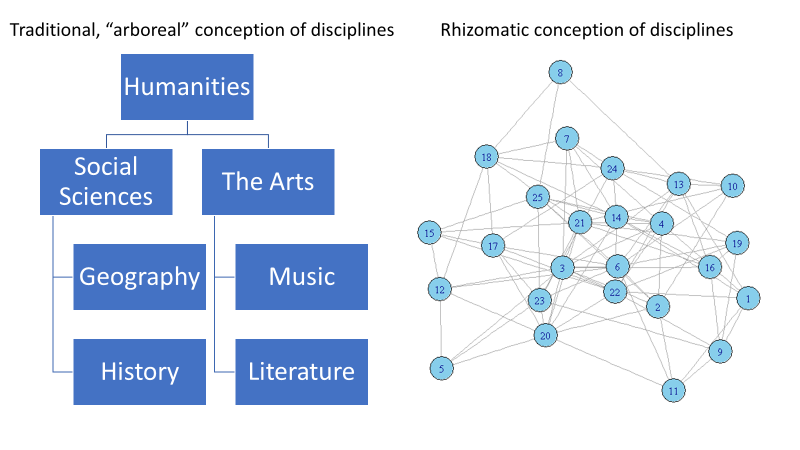

IT Service Management is a field of IS research which is widely used and popular in practice (Iden & Eikebrokk, 2013; Marrone & Kolbe, 2011). This study compares business and academic literature in the field. Since the behaviour of practitioners is influenced by the (business) literature they read (Carroll & McCombs, 2003), the comparison uncovers aspects of professional behaviour or practices not explored by academic research, termed “practice-oriented research gaps” (Müller-Bloch and Kranz, 2015).

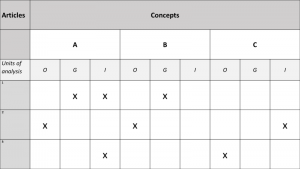

Academic literature used in the study comprised abstracts of papers from selected information systems publications, identified by database searches using keywords related to ITSM. Practitioner literature was identified through searches of selected popular press and specialist IS publications. Both sets of literature were published during a time span of 16 years (from 1 January, 2000, to 1 May, 2016). A semantic entity annotator(the technology used by resgap.com) was employed to identify topics in the two groups of identified literature, then keyword analysis was applied to identify statistically significant topics.

For each set of literature, eight of the 10 most frequently used topics also appeared regularly in the other set, suggesting that academics and practitioners view many of the same topics as highly important. However, several of the most frequently used topics differed, suggesting a degree of misalignment. Practitioner literature tended to focus on topics associated with the physical implementation and application of ITSM, while, academic literature highlighted the ideaof implementation.

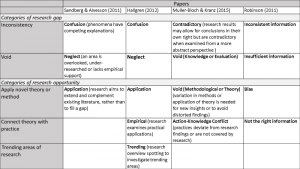

Research gaps identified

The study uncovered four broad practice-oriented research gaps. For each of these, three examples of possible research questions are provided, using a taxonomy proposed by Jarvinen (2000). They are categorised as conceptual-analytical, theory creating or testing, and artefact building or evaluating.

1. Combining Frameworks

The combination of different frameworks by organisations, to support the use of ITSM, is frequently discussed in practitioner literature. In contrast, most academic papers only consider the use of one framework at a time. Some papers do present evidence that firms combine two frameworks: CoBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies) and Information Technology Infrastructure Library (Cater-Steel, Tan, & Toleman, 2006; de Espindola, Luciano, & Audy, 2009; Lapão, 2011; Vogt, Küller, Hertweck, & Hales, 2011). However, practitioners discuss a wide range of frameworks that organizations use simultaneously.

Potential research questions:

- How does co-implementing frameworks help strengthen areas that a single framework does not cover, such as business-IT alignment, knowledge management, organizational learning, outsourcing, and competitive advantage? (Conceptual analytical)

- What theory can best reflect why different organizations consider strategic and technical factors when choosing to co-implement ITSM frameworks? (Theory creating)

- Can one develop a model that indicates the most appropriate mix of ITSM frameworks based on an organization’s specific requirements? (Artefacts building)

2. Infrastructure

Little academic research has addressed how improvements in infrastructure help organizations achieve beneficial outcomes of implementing ITSM. Further, research has not described the impact that implementing ITSM has on an organization’s infrastructure or cloud computing.

Potential research questions:

- Which ITSM processes, if any, contribute to the effective management of cloud services? (Conceptual analytical)

- As organizations increase their reliance on cloud service providers, what is the impact on the benefits that they receive when implementing ITSM? (Artefacts evaluation)

- How do ITSM frameworks help organizations implement cloud services? (Conceptual analytical)

3. Software and gamification

The practitioner literature often warns that IT departments implementing ITSM may prioritise software tools over processes, to their disadvantage. It further proposes that gamified tools may offer significant benefits in implementation. However, the advantages and difficulties associated with relying on tools when implementing ITSM are not discussed in the academic literature, nor are the effects of gamification examined.

Potential research questions:

- How can an organization best use tools to support the implementation of ITSM? (Conceptual analytical)

- Which kind of model could explain the benefits received due to the use of ITSM tools? (Theory creating)

- How effectively does gamification help train staff in the ITSM processes—specifically as it concerns content retention and engagement and staff retention? (Artefacts evaluating)

4. Regulation compliance

Practitioner literature suggests that several organizations implemented ITSM, motivated by the need to comply with regulations, such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) introduced in in 2002. The impact of regulation on the implementation of ITSM is less evident in the academic literature.

Potential research questions:

- What is the relationship between the types of regulations introduced and the ITSM organizations implement? (Conceptual analytical)

- Which kind of model could explain how organizations implement ITSM due to the introduction of different regulations compared to other rationales for adoption? (Theory creating)

- How effectively did SOX encourage organizations to pay closer attention to their IT governance?(Artefacts evaluating)

References

Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(1), 36-46.

Cater-Steel, A., Tan, W.-G., & Toleman, M. (2006). Challenge of adopting multiple process improvement frameworks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems.

de Espindola, R. S., Luciano, E. M., & Audy, J. L. N. (2009). An overview of the adoption of IT governance models and software process quality instruments at Brazil—preliminary results of a survey. In Proceedings of the 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Iden, J., & Eikebrokk, T. R. (2013). Implementing IT service management: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Information Management, 33(3), 512-523.

Jarvinen, P. (2000). Research questions guiding selection of an appropriate research method. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems.

Lapão, L. V. (2011). Organizational challenges and barriers to implementing IT governance in a hospital. Electronic Journal of Information Systems Evaluation, 14(1), 37-45.

Marrone, M., & Kolbe, L. M. (2011). Uncovering ITIL claims: IT executives’ perception on benefits and Business-IT alignment. Information Systems and E-Business Management, 9(3), 363-380

Marrone, M., & Hammerle, M. (2017) Relevant Research Areas in IT Service Management: An Examination of Academic and Practitioner Literatures. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 41(1), 517-543

Müller-Bloch, C., & Kranz, J. (2015). A framework for rigorously identifying research gaps in qualitative literature reviews. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems.

Vogt, M., Küller, P., Hertweck, D., & Hales, K. (2011). Adapting IT governance frameworks using domain specific requirements methods: Examples from small & medium enterprises and emergency management. In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems.